Pitfalls of Traditional Organisational Change Management

Traditional Change Management and its Pitfalls

For over half a century, organisational change management exists as a discipline of its own. Conventional approaches to change management are part of the syllabus of any business school. Amazon lists more than 20,000 books on this topic (counted at Amazon.com in 2023, Mar 25.).

Albeit, in most change initiatives people react with resistance and denial, and the change is sustainable. After a certain time, people return to the old status quo. According to John Kotter, Professor Emeritus at Harvard Business School...

... 70-80% of all organisational change initiatives fail.

You may doubt if this is correct or if the number is right. 1

Whether or not this number is as high as stated, or the statement is right, or wrong, conventional organisational change management has its dramatic drawbacks.

When change management has such a profound history, why does it have still so dramatic deficiencies?

Ok. — Let's phrase it in a more moderate way: only 30% of all organisational change initiatives are successful...

OK, next try: ...at least, organisational change is hard and difficult.

There are multiple reasons why change seldom shows continual impact. In my opinion the most prominent are (the order does not imply any prioritisation).

Change is run as a Blame Game. — The traditional approaches are “deficit-based”: they identify problems, analyze what’s wrong and how to fix it, they plan, and then take corrective actions. This model is predominantly taught in business schools and is presumably the default change model in most organisations. A story focused on what’s wrong invokes blame and creates fatigue and resistance. It does not engage people’s passion and experience. No one likes to be told, you worked wrong for years, or your way of working causes the current deficit of your company.

Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this point.

The business change narratives do not bridge the motivation gap between leaders and employees. — Organisations consistently tell two types of change stories. The first is the so-called “good to great” story: something along the lines of, “Our historical advantage has been eroded by intense competition and changing customer needs; if we change, we can regain our leadership position.” — In other words, the market bears the blame. The second is the so-called turnaround story: “We’re performing below industry standard and must change dramatically to survive. We can become a top-quartile performer in our industry by exploiting our current assets and earning the right to grow.” — In other words, we, the company, bears the blame. Although both of these stories seem intuitively rational, they too often fail to have the impact change leaders desire. Because of the huge gap in what managers motivate and what employees motivate. Social researchers showed that when asked what motivates them the most in their work managers and employees are equally split among five sorts of impact. 2

- impact on society (for instance, building the community and stewarding resources),

- impact on the customer (for example, providing superior service),

- impact on the company and its shareholders,

- impact on the working team (for example, creating a caring environment), and

- impact on “me” personally (my development, paycheck, and bonus).

However, what the managers care about does not tap into roughly 80% of the employee’s primary motivators for putting extra energy into the change program. Align management goals and motivations with the employees.

Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this point.

Insufficient Involvement of the People Affected. — Sure, a change story told by change leaders has to cover all five aspects that motivate the workforce. But it has much more impact, to let the employees tell the story. Treat people as Adults! You never get a committed workforce when you lurk with the final roll-out without involving them right from the beginning. And involvement does not mean, asking for comments or fine-tuning predefined concepts only.

Involvement as I understand it is when employees develop and co-create the change together with change agents or steering groups and are accountable for the success of the change implications. The why is easy: when people choose for themselves, they are far more committed to the outcome. Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this point.

Traditional Change is rolled out in a Big-Bang approach. — Conventional change approaches often start from a pre-existing change solution based on a particular problem set and business domain. Requirements are typically specified by the executives of the organisation, and maybe a small focus group of change representatives. The change itself is implemented by a Big Bang roll-out, using upfront design, and static plans.

More modern change initiatives evaluate the change improvements in "pilots" involving employees in creating the change as a kind of peer group. And, if a certain level of acceptance is reached, the piloted solution is rolled out to the broad public. This is the one-fits-all approach. However, standardisation and adopting best practices do not work any longer in our modern VUCA world. They were fine in 70-90tes of the last century. Today you have to have to accept and deal with variants, and multiple options to survive the daily business competition.

Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this impact.

Change is Disruptive. — You may think the change you want to implement is trivial, but it can have a tremendous effect on the person asking to change. Change always disrupts the status quo. Thus, in most change initiatives people react with resistance and denial, and the change is sustainable. After a certain time, people return to the old status quo. No, people do not resist to change. They welcome learning and change, but they resist being changed. People embrace change only if they accept disruption — to accept living in a volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous environment (VUCA). And to find their safe place within.

Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this point.

Change has no Start and End Points. — Traditional change initiatives realise change as a kind of project. Projects have by definition a certain start and an end. Conventional change projects are plan-driven and revolutionary. At their end is the final roll-out. They assume change can be controlled and managed with upfront planning, and change has a logical starting point because the change project has a certain starting date. The plan that gets created is based on a snapshot of organisational analysis and insights generated at a certain point in time, and from a certain point of view. But, by the time the plan is put in practice, the reality has changed, and the plan is no longer up to date. And change never stops. Change is continuous. Change is evolution. Change is life.

Conventional approaches to change management underestimate this point.

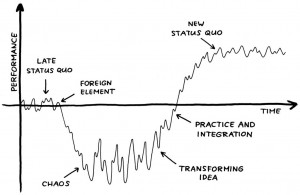

Paradox of Change. — According to the Satir Change Model, change always causes a dramatic decrease in organisational performance. Within the change new methods need to be learned, new responsibilities take time to master, and new skills take time to acquire. If the organisation is able to successfully stick with the change, then performance will flatten at the new, declined performance level. Eventually, the desired changes will have the effect of improving performance, allowing the organisation to regain the benefits of the target state.

This loss of performance leads to the so-called paradox of change.

Paradox of Change:

The less mature an organisation is, the deeper its performance drop will be once the change starts.

Paradoxically, the less mature the organisation is, the less tolerant the organisation will be for this performance drop. This “paradox of change” almost guarantees that any organisation that requires a Big Change will not be able to successfully execute on that change and will end in suboptimal outcomes.

Jeff Anderson, 2013

When organisational change has all these drawbacks, is so hard and difficult, and seldom shows sustainable pace, should we, therefore, abandon Kotter’s eight success factors, or Blanchard’s moving cheese, and everything else we know about engagement, communication, small wins, and building business cases, or all of the other elements of change management frameworks?

My answer is easy: NOPE!

Because there is an alternative: Lean Change Management. For more details, see my blog post.

Further Readings

- Jack Martin Leith: 70% of organisational Change Initiatives Fail: Is it true?

- True North Partnering: They all agree.

- Conversations of Change.au: "70% of change projects fail bollocks!"

- John Kotter: Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. Harvard Business Review, 2007.

- Michael Hughes: Do 70% of any organisational change initiatives really fail?. Brighton Business School.

- Ron Ashkenas: Change Management Needs to Change. Harvard Business Review. April 16, 2013.

- Carolyn Aiken, Scott Keller: The irrational side of change management. McKinsey Quarterly, April 2009.

: Steve Jurveston • Jurgen Appelo, .

- John Kotter stated this in his book "Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail" published in 1995. In 2007 Harvard Business Review published an equivocal article. For interesting debate on this topic refer to the internet. You find several quotes and citations about this discussion at TrueNorthPartnering.com as well. A rejection of Kotter's and his follower's judgment find for example in Conversations of Change's blog post "70% judgment projects fail bollocks!"

- For this see Carolyn Aiken, Scott Keller: The irrational side of change management. McKinsey Quarterly, April 2009. In their two famous studies, Project Aristotle and Project Oxygen Google showed how important for team effectiveness is the motivational alignment of both, team and management levels — and how they differ tremendously in Google company culture from traditional business school thinking. See also my blog posts on Psychological Safety.

Leave A Comment