Nudging – The Ideas Behind It

What is Nudging?

Nudging is a concept in behavioural science, political theory, and behavioural economics. The basic concept of “Nudging” is that a relatively subtle policy shift – the “nudge” – encourages people to make decisions that are in their broader self-interest. Nudging proposes positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions as ways to influence the behaviour and decision-making of groups or individuals.

The idea of nudging originated from earlier work by Daniel Kahneman (Thinking, Fast and Slow) and Amos Tversky, both Nobel Laureates in 2002. In 1995, the term “nudge” was coined by Dr James Wilk 1 It also drew on methodological influences from clinical psychotherapy tracing back to Gregory Bateson, including contributions from Milton Erickson, Paul Watzlawick, John H. Weakland, and Bill O'Hanlon. The theory became prominent with the 2008 publication of Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. In 2017, Richard Thaler was awarded the Nobel Prize as well.

Unlike Kahneman and Tversky, whose joint work included research into biases in regard to prospect theory, Thaler and Sunstein instead focused on identifying heuristics – tendencies for humans to think in a certain pattern, often leading to logical fallacies – and describing methods of nudging people or groups to think a certain way.

For example, how can we get more people to choose the stairs instead of the moving stairs? – Here's the nudge prepared by VW and TheFunTheory.com at Odenplan, Stockholm, Sweden. 2

Thaler and Sunstein defined a “nudge” as:

“A nudge, as we will use the term, is any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people's behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives. To count as a mere nudge, the intervention must be easy and cheap to avoid. Nudges are not mandates. Putting fruit at eye level counts as a nudge. Banning junk food does not.”

Thaler, R.H, & Sunstein, C.R. (2008), p.6.

“To qualify as a nudge, an intervention must not impose significant material incentives (including disincentives). A subsidy is not a nudge; a tax is not a nudge; a fine or a jail sentence is not a nudge. To count as such, a nudge must fully preserve freedom of choice. ...Some nudges work because they inform people; other nudges work because they make certain choices easier; still, other nudges work because of the power of inertia and procrastination.”

C. Sunstein: The Ethics of Nudging. Yale Journal on Regulation, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2015, pp. 413-450, here p. 417.

Whereas choice architecture is the design of different ways in which choices can be presented to consumers and the impact of that presentation on consumer decision-making.

Insights into nudging are also used in several countries to reduce littering. 3

It is very important to understand, that for nudging in Sunstein’s description it is mandatory to allow for free decision-making on the part of the actor being nudged. Thereby, nudges are distinct from other forms of government intervention — specifically regulations. Regulations are restrictions on the individual’s behaviour. They are used to force or coerce people to behave in a way that the government, the company or other organisations have approved of. Nudges, on the other hand, act by virtue of positive feedback loops or by way of inertia. Rather than forcing people to behave a certain way by threatening to punish them, legislators can use nudges to etch out a figurative landscape that will promote certain behaviours over others whilst still allowing for “free will” per se.

There are two very famous nudging examples in Thaler’s and Sunstein’s book.

The story of the urinal flies at Schiphol airport. – In 1970 the administration of Amsterdam Schiphol was shocked by the costs of cleaning the urinals. Fake flies were drawn near the drainage holes in airport urinals. The results were once again shocking: spillage on the bathroom floor was reduced by 80%. As Thaler explained, the reason is that men like to aim at things, so having a target to immobilize would be “fun”. Thus, the urinal flies encouraged men to be more accurate while in the bathroom — an exemplary case of the ability of nudges to engage people on a subconscious level.

The story of the urinal flies at Schiphol airport. – In 1970 the administration of Amsterdam Schiphol was shocked by the costs of cleaning the urinals. Fake flies were drawn near the drainage holes in airport urinals. The results were once again shocking: spillage on the bathroom floor was reduced by 80%. As Thaler explained, the reason is that men like to aim at things, so having a target to immobilize would be “fun”. Thus, the urinal flies encouraged men to be more accurate while in the bathroom — an exemplary case of the ability of nudges to engage people on a subconscious level.- Nudging children to choose healthy food. – Instead of banning unhealthy foods, healthy food was prominently placed to eye level and made the unhealthy food somewhat out of reach. In a similar case at a high school in New York City, changing the container that fruit had been hanging from and then adding additional light to shine on the fruit increased the sales of fruit by 54% per cent merely one week after the nudge was implemented.

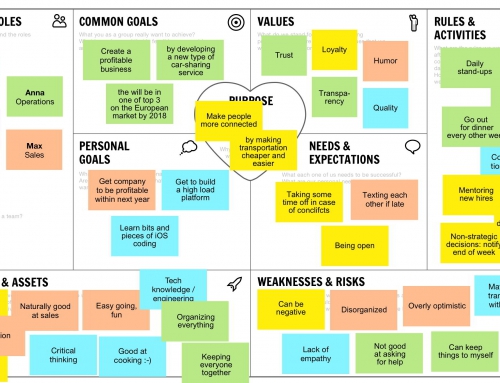

Types of Nudges

A nudge makes it more likely that an individual will make a particular choice, or behave in a particular way, by altering the environment so that automatic cognitive processes are triggered to favour the desired outcome.

Nudges are small changes in the environment that are easy and inexpensive to implement.

Basically, you can implement three different types of nudges.

- Defaults – A default option is the option an individual automatically receives if he or she does nothing. People are more likely to choose a particular option if it is the default option.

- Social Proof Heuristics – A social proof heuristic refers to the tendency for individuals to look at the behaviour of other people to help guide their own behaviour. For example, healthier food choice nudging relies heavily on this effect.

- Increasing Salience – When an individual’s attention is drawn towards a particular option, that option will become more striking, and he or she will be more likely to choose that option.

Critique of Nudging

Today, in our modern world, nudging is everywhere. You find it in marketing (e.g., placing the sweets in kid height at the cashier site), and in politics (e.g., channelling digital and analogue/print ads depending on the political preferences of suburb residents. The concept became highly political and influenced a lot of countries' governments. 4

Despite the potentially beneficial uses of nudging policies, opponents have presented serious ethical and practical concerns. 5

Nudging is seen as more and more ambivalent and conflicting. Especially at the dawn of data mining, psychological profiling and psychographic analysis (Cambridge Analytica), and potential influencing political elections.

It has been remarked that nudging is a euphemism for psychological manipulation as practised in social engineering.

And that nudging is highly manipulative despite its appeal to the free will of the person to be nudged.

In the abstract of his paper Misconceptions About Nudges, Sunstein argues about misconceptions and rises high principles.

"Some people believe that nudges are an insult to human agency; that nudges are based on excessive trust in government; that nudges are covert; that nudges are manipulative; that nudges exploit behavioural biases; that nudges depend on a belief that human beings are irrational; and that nudges work only at the margins and cannot accomplish much.

These are misconceptions. Nudges always respect, and often promote, human agency; because nudges insist on preserving freedom of choice, they do not put excessive trust in government; nudges are generally transparent rather than covert or forms of manipulation; many nudges are educative, and even when they are not, they tend to make life simpler and more navigable; and some nudges have quite large impacts."

Further Reading

- Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein: Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2008.

- Cass R. Sunstein: The Ethics of Nudging. Yale Journal on Regulation, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2015, pp. 413-450.

- Cass R. Sunstein: Misconceptions About Nudges. Sep 2017.

- Daniel Kahneman: Thinking, Fast and Slow. Penguin, 2012.

- Raphael Potter: Nudging – the practical applications and ethics of the controversial new discipline. The Economics Review at NYU, March 23, 2018.

- Habitry: The Nagging Issues of Nudging. Medium.com, Oct 23, 2017.

: Frank Van De Ven, via Medium.com • WissensDürster via Wikimedia Commons, .

- James Wilk: Kaleidoscopic Change. Univ. Oxford.

- Volkswagen developed together with the advertising agency DDB Stockholm's Rolighetsteorin.se or "Theory of Fun" campaign which showcases efforts to get people to change by simply making things more fun. To encourage people to take the staircase instead of the escalator, they converted a set of steps at the Odenplan subway station in Stockholm into working piano keys.

Claire Bates: Scaling new heights: Piano stairway encourages commuters to ditch the escalators. DailyMail, 12. Oct. 2009,

Volkswagen, AdAge. - Talking bins in the US, Zero Waste Scotland Limited: Nudge Study – promoting the use of litter bins and Julia Kolodko, Daniel Read, Umar Taj: Using Behavioural Insights to reduce littering in the UK. CleanUp.Britain, Nugeathon.com, Jan. 2016.

- Prime Minister David Cameron and President Barack Obama sought to institutionalize “nudge units” to advance domestic policy goals during their terms (e.g. to move people away from their bad health habits), see Andy McSmith 2010.

In 2010 the UK Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) was set up. It is working in Australia and there is also an office in Wellington, New Zealand.

England, Germany, and Switzerland changed on 6th March 2018 the existing 'opt-in' consent for organ donation to ‘opt-out’ consent. - Habitry 2017, Potter 2018, and see the literature cited in Wikipedia article.

Leave A Comment